How Biden Traded Transformers for Heat Pumps

And what to do now

Today, Green Tape is publishing its first guest post, authored by Charles Yang. Charles spent the past two years as an AI & Supply Chain Policy Advisor at the Department of Energy, and is now incubating a new project on industrial policy.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in guest posts do not necessarily reflect the official position or views of Green Tape.

In America’s race to electrify everything from cars to manufacturing, it has started to run out of transformers. These critical components, which regulate voltage throughout our power grid, now have multi-year wait times and prices that have nearly doubled since 2020.

We shouldn't be in this situation. Back in 2022, the Biden administration had an opportunity to use Defense Production Act (DPA) funding to boost domestic transformer manufacturing capacity. Instead, it chose to direct its $250 million in DPA authority towards heat pump production. This was a disastrous misstep — and now the U.S. is stuck playing catch-up.

Tracing the Shortage

For the past 15 years, the U.S. power grid has seen flat load — that is, flat demand. This was largely the result of the 2008 economic downturn, combined with investments in demand response and load shifting that allowed for more efficient utilization of grid infrastructure.

But the U.S. is now entering an era of load growth, driven by data centers, booming demand for electric vehicles, and the on-shoring of domestic manufacturing.1 This is a good thing — a growing grid is a sign of a growing economy. But the U.S. faces significant barriers to bringing the requisite new power online: sluggish interconnection queues; permitting (famously); and the focus of this article, a shortage of power grid transformers.

A Primer on Transformers

Transformers are the backbone of the U.S. power grid. The efficiency of power transmission depends on the voltage level, with higher voltages allowing for more efficient long-distance transmission. This is where transformers come in, increasing the voltage at power generation sources before electricity travels along transmission lines to load centers. At these load centers, transformers then "step down" the voltage to safer, lower levels for distribution, until it eventually reaches homes at 240 volts. Without transformers to manage these voltage changes, the power grid would be fundamentally constrained, unable to economically connect new generation or new loads.

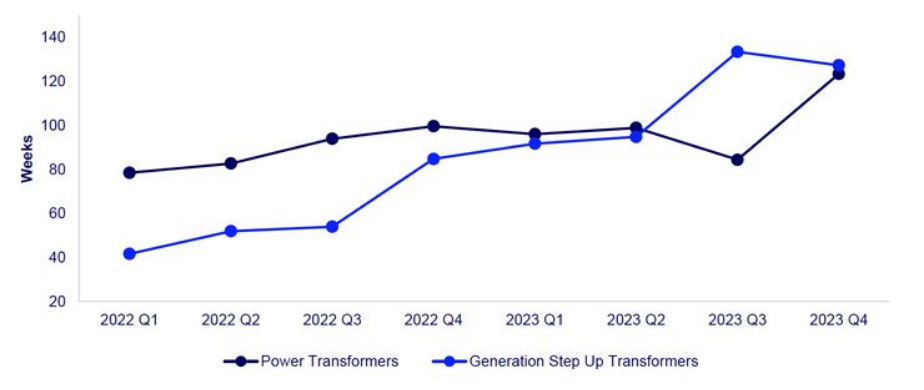

Today, the U.S. is facing a severe supply shortage in the transformer market. Prices are skyrocketing, while lead times for Generator Step-Up (GSU) transformers have nearly tripled since 2022.

So — how did we get here?

First, the U.S. grid is aging, and our transformer infrastructure is no exception. U.S. transformers are more than 30 years old on average, and this infrastructure debt is beginning to come due, driving an up-cycle in demand.

Second, America is entering a new phase of electrification. Electric vehicles, rooftop solar, and heat pumps have significantly increased loads on distribution circuits, accelerating the need for upgrades. So too has the push to onshore manufacturing, combined with the rapid buildout of utility-scale renewables.

Third, the U.S. lags far behind competitors such as China when it comes to electrical manufacturing. For example, there is only one U.S. producer of grain-oriented electrical steel (GOES),2 a key component of transformers. Foreign dominance of GOES and other critical transformer components have forced U.S. producers to depend on foreign supply, hurting their ability to compete with more vertically-integrated competitors abroad.

The combination of these manufacturing shortages and demand spikes has created a perfect storm that has disrupted the deployment of new load centers. This is a huge national and economic security concern: a growing power grid is critical for industrialization, which is why China’s grid has been growing at 6-7% year-over-year. By contrast, the US’s grid is expected to grow at just 2-3% per year over the next decade, even with the advent of hyperscalers and other load growth drivers.

Biden’s Misstep

The federal government has long been aware of the looming transformer crisis. In 2022, President Biden delegated DPA Authority to the Department of Energy (DOE) to support domestic production of components related to (1) solar, (2) heat pumps, (3) building insulation, (4) hydrogen, and (5) transformer and grid components.3 Two months later, Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, which included $500 million for DPA funding. Half of this funding went to the Department of Defense for critical minerals, and the remaining half went to the DOE.

At DOE, the growing backlog in transformer orders was a key area of concern. In 2022, the Department released a dedicated supply chain report on large power transformers (LPTs). In 2023, DOE released a progress report (which I helped co-author) that highlighted distribution transformers, LPTs, and other grid components as critical areas for supply chain investment. DOE wasn’t alone, either: Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security published a 400-page report on transformers and national security back in 2020.

But at the same time, climate nonprofits — and in particular, Rewiring America — were lobbying Democrats in Congress to use the DOE’s $250 million for heat pump manufacturing instead of transformers.4 The nonprofits won. Despite the clear supply-side challenges presented by electrification and load growth, the Biden administration decided to use one of the few tools available for boosting transformer capacity to increase load growth even further.

Load growth aside, there was also the more fundamental question of whether heat pump production is really a critical industry to onshore. Unlike other energy technologies, heat pumps are typically produced in the same country or continent where they are consumed. The notion that China would strategically restrict heat pump compressor exports to the US, then, strains credulity. But this logic fell on deaf ears. In an effort to satisfy a small group of climate progressives whose only focus was near-term carbon-counting, the Biden administration was ignoring our transformer shortage and spending taxpayer dollars to onshore a commoditized appliance industry.5

What To Do

With transformer shortages already impacting our grid reliability, immediate action is crucial.

As a first step, Congress should pass Senators Moran and Cortez Masto’s CIRCUIT Act. The CIRCUIT Act extends a 10% tax credit to transformer manufacturing, which will help domestic transformer production to “pencil out” and support the struggling industry as it looks to recapitalize.

Second, the executive branch should repurpose the remaining DPA funding at DOE (~$14M) for transformer manufacturing rather than heat pump manufacturing.6 This is long overdue, and would support the new administration’s national security focus.

Third, the administration should use DOE’s Electricity Advisory Committee (EAC) convening authority to develop common standards for transformer procurement. The default today is that each utility develops different standards and requirements for even commonplace distribution transformers, making standardized sales and manufacturing difficult. Some of this industry coordination and standard-setting work is already underway through the EAC.7

Finally, the administration should leverage the DOE’s Office of Electricity to fund industry R&D around solid state substations, adaptable LPTs, and other advanced transformer materials. All of these efforts could enhance the efficiency and production of transformers.8

The new Republican trifecta has a variety of policy tools available for addressing the transformer shortage, from manufacturing incentives to procurement standards. The only question is whether we'll finally choose to use them.

Relatedly, there was significant controversy around DOE’s transformer efficiency standards, which initially proposed to increase the required electrical efficiency of transformers so as to require a shift from GOES to amorphous steel, a newer form of electrical steel. But doing so would also exacerbate shortages, as utilities would be even harder pressed to find transformers that qualify under the new rule. DOE ultimately pushed out the compliance timeline to give more time for sourcing higher efficiency electrical steel.

Fun fact: while DOE’s DPA authority on energy manufacturing technologies is new, DOE has had DPA authority for supercomputer components for some time now.

Rewiring America’s modeling on IRA demand incentives for heat pumps were also criticized by HVAC contractors as overly optimistic and political

Not only was this a poor step on bad industrial policy, it also contributed to the politicization of DPA. The use of DPA for heat pumps was heavily criticized by Republicans, and some Democrats in Congress. This move was part of a broader and frankly radical expansion of DPA use in the Biden admin, including in the now-rescinded AI executive order for reporting on frontier model training. The longer-term ramifications of this expansive DPA use remain to be seen, given the upcoming expiration of DPA authority in September 2025 that will need to be renegotiated through Congress.

And it is always possible that some of the announced projects may not move forward, returning some funding.

The lack of standardization around transformer designs, particularly distribution transformers, is why I’m baffled by ideas of a “transformer stockpile”. While demand whiplash from bursts of federal infrastructure spending, present and historical, is an issue, transformers are not commoditized to the point of being fungible.

Note DOE’s FY25 budget request included an 18% increase in funding for this program. Congress would be wise to support this kind of applied R&D in a critical technology.

>heat pumps have significantly increased loads on distribution circuits

I'm not certain how true this is. Heat pumps are still a lot more efficient than traditional A/C for cooling, thus it can be a net new appliance while displacing less efficient AC within the same power envelope. For A/Cs sold within the last decade or so they would hypothetically have a SEER rating of 13-14, and many of the new heat pumps range from 19-20 as a starting point, which is a 38% reduction in electricity usage off the bat.

Using heat pumps for heat as well vs. a fossil fuel admittedly is net new electricity usage, but if it displaces electric resistance space heating that is a major efficiency savings there too.

Notably heat pumps displace load overall and at the times of highest stress (really cold and hot days respectively), so in some ways they are a cost reduction center, not an added stressor to the grid. Trying to shed/shape load around those rare thermal extremes is very expensive and heat pumps actually reduce the grid's struggle in performing during those periods. This is unlike the mode shift from EVs which just as a form of expenditure of energy is strictly additive in shifting from ICE to EV.

At least $43 million in 48C Advanced Energy Project tax credits were awarded to companies investing in various kinds of transformers, including $18m in support of an overall $150m investment by Siemens to begin manufacturing large power transformers in the U.S. for the first time in the company's history. "At least" because companies had to voluntarily self-disclose that they won the allocated credits, due to taxpayer privacy rules. Hard to see how an additional ~$200m in grants (with attendant NEPA requirements, which tax credits don't have) would be massively more...transformative. (Had to, it was right there.)