A Turn Lane in Rhododendron

A NEPA/NHPA Story

Back in the late ‘90s, a short section of road near Rhododendron, Oregon was particularly prone to car crashes.

As the city of Portland had grown, Route US-26, the regional highway that connects the city to the ski and recreation areas on Mount Hood, had become increasingly congested.

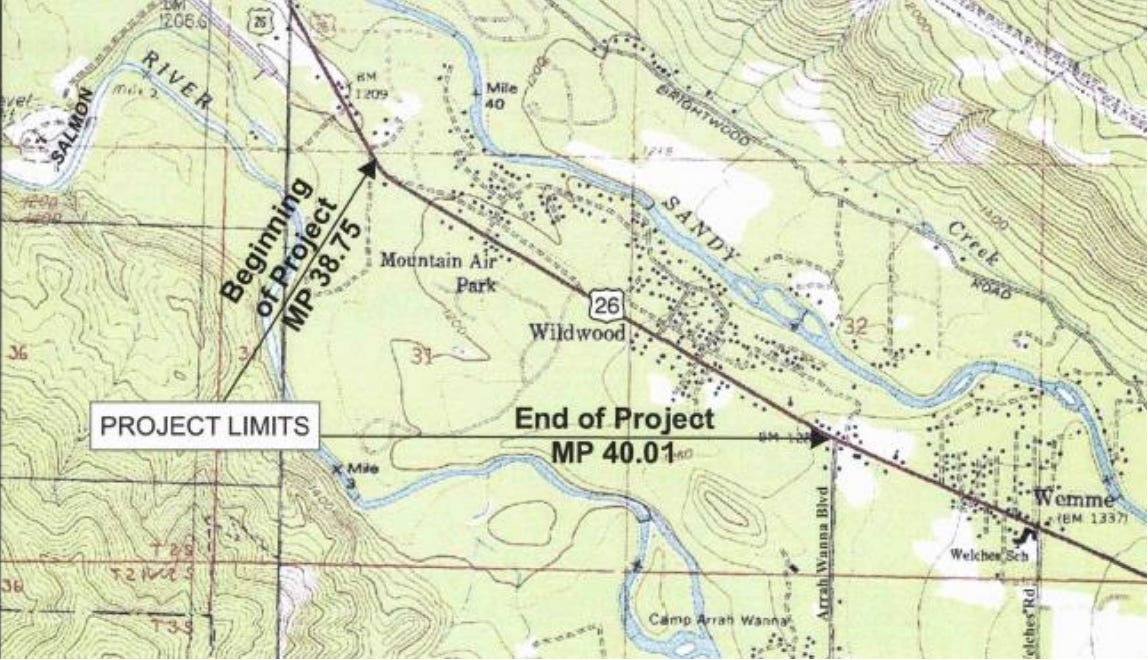

Between the villages of Wildwood and Wemme in particular, these increases had created dangerous driving conditions; in a draft NEPA document exploring highway infrastructure upgrades in the region, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) noted that the accident rate on US-26 was twice as high as those in other primarily rural, non-freeway highways.

So, in 1998, over 650 residents, recurrent visitors, and patrons of local business signed a letter to the Oregon Department of Transportation expressing “great concern and fear for their personal safety” due, in particular, to “the lack of a left turn [lane]” between Wildwood and Wemme.

Approximately forty driveways and side streets fed into those 1.26 miles of highway, creating a safety hazard for cars turning onto and off from the highway. Cars turning off the highway had to stop in the fast lane to wait for a gap in oncoming traffic; cars turning onto the highway had no median to enter as they picked up speed.

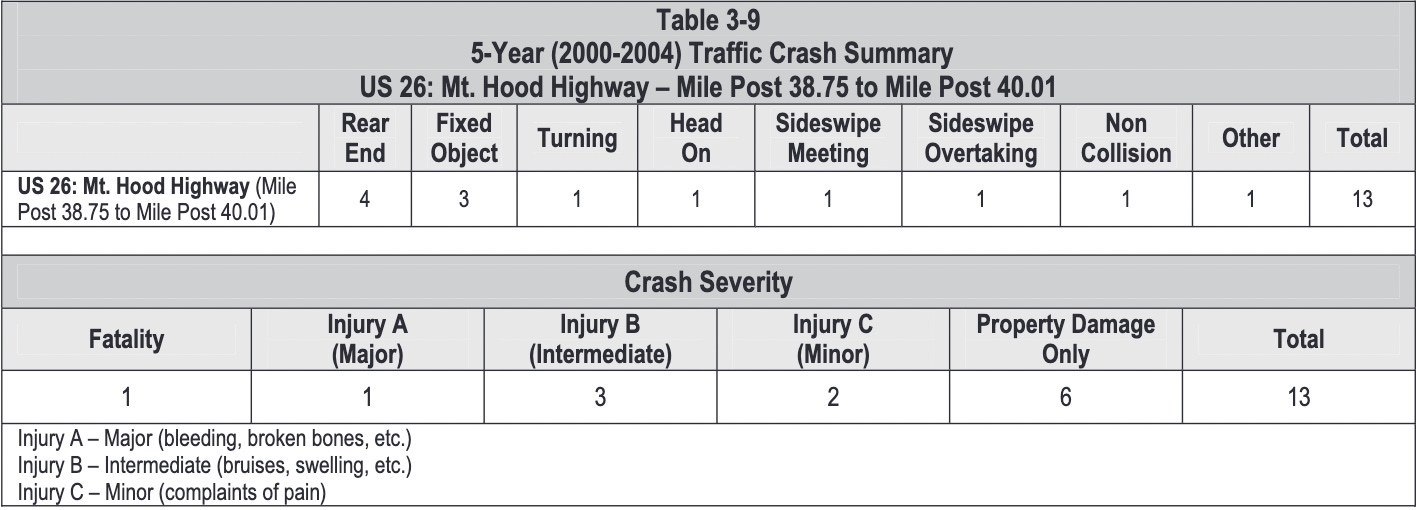

During the five year period surrounding the letter to ODOT, there were 14 crashes along that section of road – two of them fatal.

In response to the letter, ODOT began scoping solutions, with the goal of widening the road to match the sections of highway to the east and west.

But this project was technically under FHWA jurisdiction, and would thus require NEPA and National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) review.

The Backdrop

This part of Oregon is, and was, infamous for its public opposition to development. Two decades prior, the FHWA had set off on a NEPA review for a highway widening effort, releasing its Draft EIS a year later (oh, the good old days of a one year timeline to Draft EIS). As part of the review, FHWA had sent out an archaeologist to the project area, who determined that it did not contain any sites “listed in, nominated to, or determined eligible in the National Register [of Historic Places.” That is, it was not a ‘historic property’ under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and thus didn’t require formal NHPA review.

But after publishing the Draft EIS, FHWA hosted another series of public comments. It primarily received input from an organization named Citizens for a Suitable Highway (CFASH), a local group led by one Michael P. Jones. During a hearing on the project, Jones presented a slide show which depicted photos of “stone pillars” and a “pioneer grave” which he alleged were eligible for protection.

So FHWA sent out an archaeologist to look at the potential pioneer grave. Quoting from an ensuing court case directly:

They found “no subsurface disturbance accompany[ing] the placement of the rock pile on the surface. No skeletal material or other cultural objects were found.” Because the rocky deposit beneath the rock pile had not “been previously disturbed in any way,” the archeologists wrote that they “were in complete agreement that there was no evidence of disturbance of any kind beneath the rock feature, and that the possibility of a burial beneath the stones has been shown to be extremely remote.”

Based upon our investigations described herein,” Archaeologist Richard M. Pettigrew concluded, “I recommend no further investigation of the rock feature, which has no demonstrated archaeological significance and does not in my judgment appear worthy of either protection or mitigation.

The final cultural resources report did not discuss the rock feature. But in early 1986, Pettigrew received a letter from CFASH threatening to sue “if the potential gravesite is further disturbed.”

And the next year, ODOT regional engineer Rick Kuehn spent several months working with Jones and CFASH to address their concerns. Kuehn painstakingly kept a document describing the over 70 issues that they discussed, summarizing the actions to be taken and cost implications for each issue.

Among them: In the Dwyer area, “the north pavement edge [would be] moved 15 feet to the south… by eliminating the left-turn refuge.” Sound familiar?

Finally, in 1991, ODOT again met with Yakama Nation Tribal Council Chairman Wilferd Yallup and representatives CFASH to discuss the project. According to reports:

Yallup opened the meeting by indicating that FHWA had paved over a burial site between Goldendale and Toppenish in Washington State, and that he did not want that to happen again.

When [ODOT Engineer] Bartel asked Yallup, “Are you saying that there is a burial ground on this project?,” Yallup answered, “Yes,” and Jones added, “Rhododendron to the bridge.”

But when Bartel responded, “Where exactly? Can you be a little more specific?,” Jones interrupted, “[W]e’re not going to get down to specifics. If you want like pinpoints, you know, we’re not going to do [that].”

Wildwood to Wemme

So, this was the backdrop in the early 2000s as ODOT began scoping its 1.26 mile Wildwood to Wemme highway safety project.

As court documents note, “Internally, ODOT staff were sympathetic to the safety issues, but an ODOT project manager recounted how the ‘community went nuts when this section of highway was proposed for five lanes in the 1980s. . . . Because of the public uproar, the highway was reduced to four lanes.’”

By 2004, ODOT had determined it would need to prepare an environmental assessment under NEPA. And, citing the 1985 Draft EIS, it determined that it would have to reassess historic resources, and that the project would thus require official NHPA review.

So ODOT sent out another team of archaeologists. This team, too, confirmed Pettigrew’s report that the rock cluster alleged to be a grave did not have historical significance. And ODOT sent out four newsletters and postcards advertising three public hearings. They hosted an open house, and invited Michael P. Jones. Later that year, ODOT hosted another open house to discuss project alternatives. They invited Jones again.

Per reports:

ODOT’s summary of the meeting indicated that “‘people’s lives ahead of trees’ was a common theme.” “Alternative 1: Widen North” received the most favorable public response while the “No Build” alternative received the least favorable response.

Several attendees submitted the same written comments, one of which asked ODOT to disregard those submitted by people who were not “impacted by the current danger to life and property” by the lack of a center turn lane. One person handwrote, “This means Michael P. Jones!” next to this comment.

In 2006, ODOT hosted a third open house. They invited Jones again.

Three months later, ODOT sent postcards and mailers indicating it was focusing on the “Widen to the North” alternative most favored by the public, advertising an upcoming open house and linking to an ODOT website with more information. The mailer included preliminary environmental findings, and allowed people to request copies of the forthcoming Draft EA. Jones requested a copy.

In August, ODOT published the Draft EA. In the fall, they hosted another meeting. Only 16 people attended, and only 5 made public comments. One simply said: “To the folks at ODOT[,] a hearty thanks for all the hard work. Your determination will carry this project through.”

ODOT issued the Revised EA and FONSI on January 25, 2007, selecting the widen-to-the-north alternative. They sent the final project notice to Jones.

It’s Never Over

In January 2008, Jones resurfaced – this time with Carol Logan, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde who claimed to represent tribal interests. Logan and Jones began bombarding FHWA and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) with demands for new NHPA reviews.

ODOT reached out to Grand Ronde, who clarified that Logan wasn’t speaking for them. Per their Cultural Protection Coordinator: “Carol is not representing the Tribe... she is working as a private individual in concert with Michael Jones. The tribe’s official position is that ODOT has done and followed the 106 and NEPA process. We have no fault with what they have done.“

By May 2008, Jones had recruited Wilbur Slockish and Johnny Jackson, who identified themselves as “hereditary chiefs” of the Klickitat and Cascade tribes – bands within Yakama Nation that are not themselves federally recognized tribes. They submitted memoranda claiming the Dwyer area contained sacred burial sites.

ODOT determined that it didn’t see a reason for further consultation based on the scope, and concluded it had satisfied its NHPA duties. Construction began in early 2008, and was completed later that year, ten years after scoping began.

In that time, there were tens of crashes, multiple injuries, and at least one death along the section of road. Most of the reported crashes that occurred in the project section were attributed to the lack of a left turn refuge on the highway.

The Aftermath

I’ll note here that this story really never ended. In July 2008, after construction had begun, Jones called an archaeologist claiming the “site” had been vandalized. When she investigated, she found “the rock cluster in scattered and disturbed condition” but concluded it “appears to still have no other associated objects or features such that it could be identified as a cultural resource.”

Jones filed a lawsuit in October 2008. The case dragged on for 13 years. In February 2021, the district court granted summary judgment to the agencies. The Ninth Circuit dismissed the appeal as moot in November 2021. And finally, in October 2023, a final settlement was reached.

What started as hundreds of residents pleading for a left-turn lane to stop fatal crashes in 1998 became a 25-year saga. The safety improvements that should have taken months were delayed by nearly a decade of process, followed by 15 years of litigation over, to quote Archaeologist Richard Pettigrew, a “pile of rocks.” The left-turn lane was built, but at enormous cost in time, money, and unfortunately, human life.

The stone pillars Jones fought to preserve were damaged during relocation. They were then repaired by a contractor – the same contractor, as it would happen, who had previously repaired the pillars after one was struck by a car crash years earlier.

Man, that guy sounds like a real piece of… *work*.

An author wrote this a while back saying that the US isn't a democracy, it's a vetocracy. The 1% or even the individual can veto anything.