Revisiting Pro-NEPA Studies

Leaning into the drama

Every few months, someone in the environmental justice world comes across one of two studies: David Adelman’s “Permitting Reform’s False Choice” or John Ruple’s “Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden.” After reading the executive summary, they immediately conclude that they have uncovered a vast conspiracy and take to Twitter to declare that NEPA Was Never A Barrier to Energy In the First Place.

Infrastructure Twitter was dragged through another round of this discourse recently, so I figured it was high time to take a closer look at both the Ruple and Adelman studies. In both cases, the data is perfectly fine, and generally provides evidence in favor of permitting reform. The authors’ interpretations of this data is where things fall off a cliff.

Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden

Ruple’s study analyzes 1,499 federal court opinions involving NEPA challenges from 2001-2013. He comes up with two key findings:

Only about 0.22% of NEPA decisions (1 in 450) face legal challenges

Less than 1% of NEPA reviews are environmental impact statements (EISs), and about 5% of NEPA reviews are environmental assessments (EAs).

For permitting reform advocates, these statistics sure seem damning. Indeed, we often talk about the litigiousness of NEPA as the core problem with the law, pointing to the time, cost, and uncertainty that litigation creates for infrastructure developers.

But in “Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden,” Ruple makes the same error that he’s made throughout his work on permitting: he takes the average volume of litigation across all NEPA reviews and makes a conclusion about NEPA’s impact on infrastructure in particular. In other words, his denominator is wildly inflated.

Ruple’s dataset includes NEPA reviews at every level of stringency: categorical exclusions (CatExes), EAs, and EISs. And as Ruple himself points out, around 95% of NEPA reviews are CatExes. This is because NEPA is triggered by almost every federal action, and thus CatExes are required for everything from federal hiring to, yes, picnics.

Now, this may come as a shock to some, but the government rarely gets sued for its sandwich-eating practices. More broadly, the nature of categorically excluded activities means that CatExes sees near-zero litigation rates.

By contrast, energy infrastructure very rarely falls into the CatEx bucket. In fact, clean energy projects going through NEPA typically must complete an EIS—the highest level of review—and otherwise complete an EA. These projects are much, much more likely to be sued.

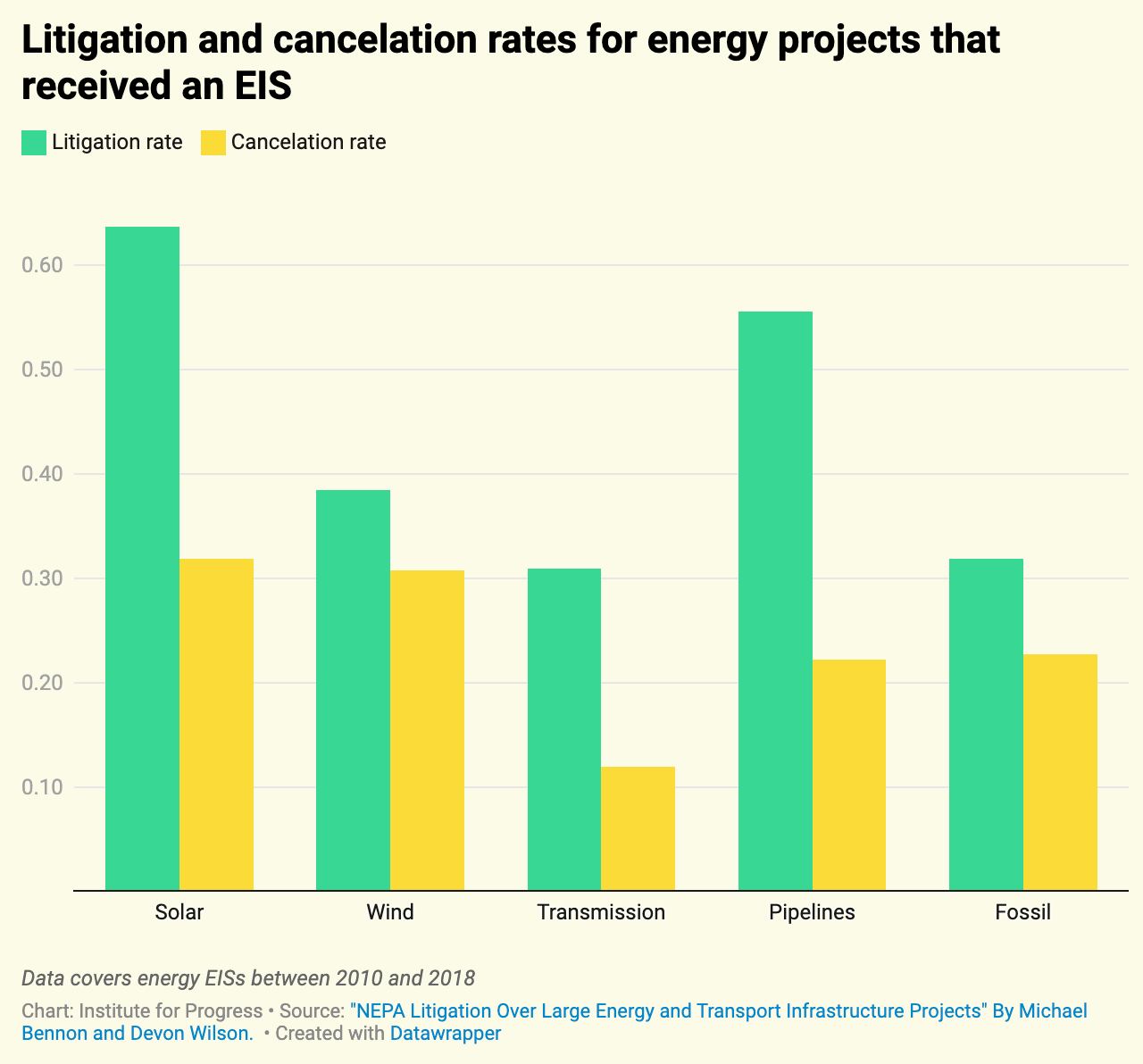

The actual litigation rates for energy infrastructure, then, are markedly higher than Ruple’s 0.22% statistic would suggest. Last year, Stanford University’s Michael Bennon and Devon Wilson analyzed the hundreds of infrastructure projects that completed EISs from 2010-2018. Their findings are remarkable: solar, pipeline, wind, and transmission projects saw litigation rates of 64%, 50%, 38%, and 31% respectively. The cancellation rates for each of these project types were also extraordinarily high, ranging from 12% to 32%.

To be clear, Bennon and Wilson’s study focuses specifically on EISs, the most stringent level of review. But this is a more appropriate scope than Ruple’s, as EISs are the norm for clean energy projects, not the exception. For example, Resources for the Future’s study of solar projects built on federal land from 2009-2021 found that 61% underwent an EIS, while the remaining 39% underwent an EA. None were categorically excluded.

So by any measure, energy infrastructure projects undergoing NEPA are litigated at remarkably high rates. And while Ruple’s data is likely accurate across all NEPA reviews, it tells us nothing about NEPA and infrastructure.

Permitting Reform’s False Choice

Adelman's study examines environmental reviews and permitting for renewable energy projects from 2010-2021. Like Ruple, Adelman presents findings that appear to minimize NEPA's impact on clean energy development: less than 5% of wind and solar projects required an EIS, and in total only 29 EISs were required for wind while 36 were required for solar.

The basic flaw in Adelman’s analysis is that he sees the low percentage of renewable projects that undergo NEPA as evidence that NEPA isn’t a big deal. In reality, the exact opposite is true. My friend Aidan Mackenzie explains this in a recent piece for IFP:

The 5% statistic can be explained as a selection effect. Similar to “venue shopping” in the legal system, “jurisdiction shopping” is the practice of choosing a project location to find a friendly regulatory environment. The high costs of federal permitting, for which NEPA review is the largest burden, incentivizes developers to find locations that avoid triggers for NEPA review. This leads to a strong selection effect, where the costs of NEPA cause developers to avoid developments that would invoke the law.

Take utility-scale solar developments as an example. These projects consistently avoid federal lands and the associated NEPA reviews, despite federally managed lands covering much of America’s best solar resources. For example, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico have some of the best solar resources in the country, provide friendly tax incentives, and proactively prevent local prohibition. Both New Mexico and Arizona scored highly for ease of grid interconnection. But all three states have relatively little solar development and solar developers seem to dodge federal lands as much as possible. While many factors contribute to selecting project locations, the evidence suggests that federal permitting — for which NEPA is the tip of the spear — plays a significant role.

You can see this dynamic when you compare the US solar irradiance map (where solar potential is highest) to the map of the US solar boom. You’ll note that solar development is not concentrated where the potential is highest—and that our solar potential is highest on federal land, where NEPA is triggered. This is no coincidence.

As I noted on Twitter, Adelman admits that this NEPA avoidance strategy is a key part of the development picture, writing that “Project selection and development may be channeled around potential triggers for environmental reviews and permitting, which can mitigate environmental impacts but may also lead to less-productive projects.”

In response to my tweet, Erik Anderson of Candela Renewables added the following:

A final datapoint here: the one type of energy infrastructure that is particularly hard to site away from federal land is transmission. Unsurprisingly, the rates of NEPA review for transmission are very high—per Niskanen and Clean Air Task Force, more than a quarter of all new transmission line miles from 2010-2020 underwent an EIS.

Final Thoughts

There’s no question that the case for NEPA reform would benefit from a great deal more publicly available data. We’ll probably get significant legislative reform before we get a good estimate of the true cost that permitting imposes on developers. But the data we do have is conclusive: NEPA is a major problem for energy development.