How to Rewrite an Environmental Law in 30 Days

Breaking out the flowcharts

When President Trump issued the executive order nullifying all NEPA regulations on his first day in office, he set in motion a 30-day shot clock, at the end of which the now-defanged Council on Environmental Quality will have to issue entirely new NEPA guidance. The mandate, in short, is to rewrite one of the country’s most complex environmental laws, paring back its requirements wherever possible, in under a month.

As soon as we saw the news, my friend Aidan at IFP and I started thinking about what this new guidance could look like. The result is our new paper, published yesterday.

For all the wonky details, readers should just go check out the paper, but I thought I might share some higher-level thoughts here.

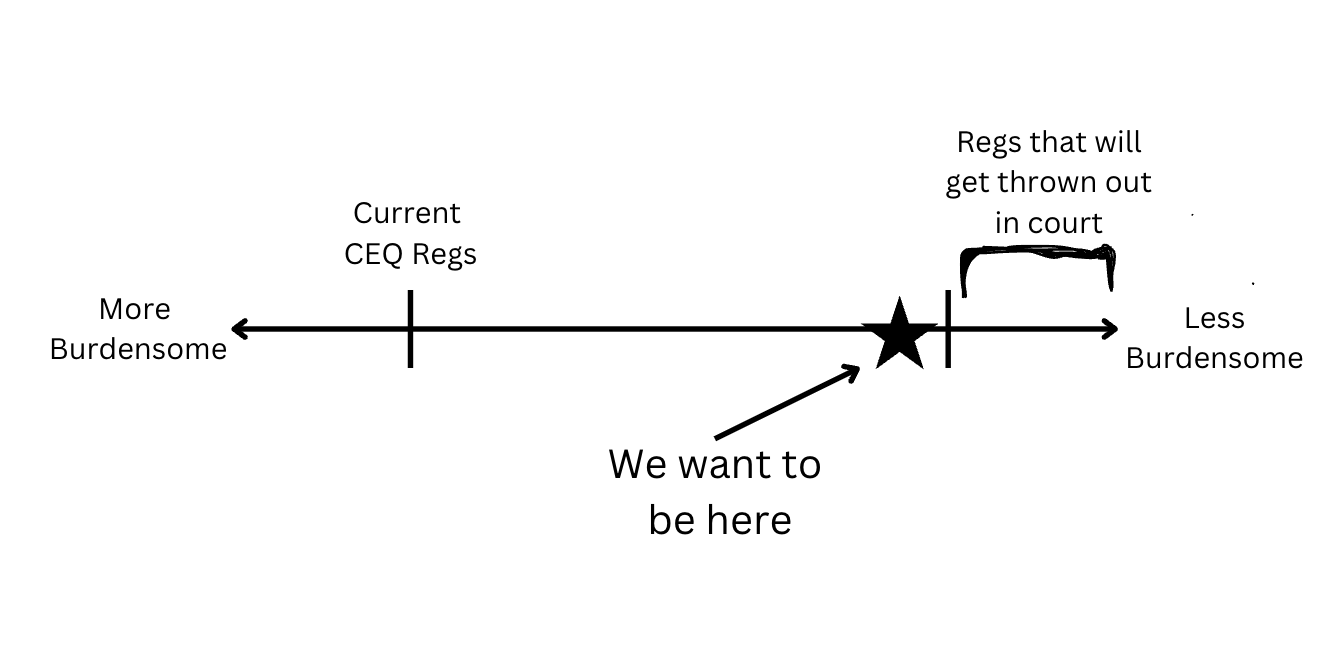

The success of the NEPA EO will come down to implementation. Throwing out CEQ regulations is great, but only if agencies’ replacement regulations are a) less burdensome and b) survive the inevitable court challenges. In the post-Chevron era, the best way to do this is to hew closely to the language of the statute.

You can think about this like a continuum, where the left side is “more burdensome” and the right side is “less burdensome.” We want to move right from the current CEQ regulations – but eventually we’ll reach a line where our new interpretations of the law are so aggressive that they’re likely to be thrown out in court. We should stop here, or risk being sent back to where we started.

The incredible stroke of luck is that the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (FRA) changed the language of NEPA. At the time of its passage, the FRA didn’t seem like much – in fact, many permitting reform advocates, myself included, cast it aside as a nothingburger. This was in large part because the CEQ’s implementation of the FRA’s changes did almost nothing to change the status quo, in some cases going as far as to drop some of the FRA’s new language. But when you remove CEQ regulations from the picture – as the recent executive order has done – and just compare the FRA to the original text of NEPA, it’s very clear that the FRA provides a clear mandate to narrow the scope of NEPA review.

Before I explain this, let’s first review how NEPA works.

The level of required NEPA review is determined according to three tests:

If an action is determined to be a “major federal action,” NEPA is required. Otherwise, NEPA is not required.

If a major federal action “normally” does not have a “significant effect” on the environment, it may be categorically excluded from the full NEPA process. Otherwise, an environmental assessment (EA) or environmental impact statement (EIS) is required.

If the “significant effect” is not “reasonably foreseeable,” an EA is required. Otherwise, an EIS is required.

Given that NEPA’s requirements turn on these three tests (represented by the yellow circles in the graph above), the goal of revised NEPA regulations should be to:

Reinterpret “major federal action” to narrow the set of actions that trigger NEPA in the first place

Reinterpret “normally” and “significant” to expand the set of actions that can be categorically excluded

Reinterpret “reasonably foreseeable” to narrow the set of actions that require an EIS

The beauty of the FRA is that it offers new definitions for all three of these tests compared to the original text of NEPA.

For example, NEPA’s original text did not define “major federal action.” The CEQ regulations that followed then interpreted the term to mean “actions … which are potentially subject to federal control and responsibility.” By contrast, the FRA defines a major federal action as one “subject to substantial federal control and responsibility.” This is clearly a narrower definition.

Similarly, NEPA’s original text did not explicitly provide for categorical exclusions, while the 1978 CEQ regulations allowed for categorical exclusions when actions “do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment.” By contrast, the FRA provides for categorical exclusions when, “a category of actions… normally does not have a significant effect on the human environment.” Again, this creates an opportunity for streamlining, as “normally” represents a comparatively lower standard.

Finally, NEPA’s original text requires EISs for actions “significantly affecting the quality of the human environment,” and the 1978 CEQ regulations defined “significantly” according to a would-be-comical-if-it-weren’t-such-a-problem “context and intensity” standard, which weighs everything from the controversy and uncertainty of an action to cumulative effects. By contrast, FRA requires an EIS when an action “has a reasonably foreseeable effect” on the environment. Here, too, there is opportunity for reform.

The topline from the paper is this: Our proposed new NEPA framework could substantially reduce the number of actions that require NEPA in the first place and the number of actions that require an EIS, while radically reducing the number of actions that require an EA. I’m very excited about it. Go give it a read!